The exhibition title, a statement delivered without judgement, recognises the suffering woven into being, as well as the improbability of its endurance. As Zibaya acknowledges,

It sometimes feels as though the price of being human is too high. I think sometimes that pain is greater than happiness. We don’t forget pain, despite the behavioural systems we develop – working, getting a job, waking up, etc. We are all somehow held by a responsibility that we did not sign up for, or we are not aware of, but we find ourselves in it, and we must maintain it.

In his experience of the city, Zibaya witnesses the acts of violence – economic, social, political, personal, emotional – expressed through the lives of the city’s inhabitants. And yet his title is cause for pause; a reflection of where we have come from, and how survival seems to withstand despite countless inflictions:

I am very aware of space, the state of being alive and the state of decay. You can go to those areas where people are peeing, and the smell is overwhelming. But even those spaces have some energy (depending on who you talk to!). It is almost poetic, as if the space has its own memory. I have found so much beauty and so much poetry in these spaces.

And despite the government’s washing trucks, there’s this persistence. There are these colours that can come out, and this erosion can be revealing of a human existence. I don’t think this revealing is ugly. The abstraction in those spaces is interesting, even though it may be a beauty that some of us are not even aware of.

The exhibited artworks witness this very idea of destruction and persistence through encounters of the City and mark the idea of a “call and response”. They are the expressions of both a spectator and an actively engaged participant in urban life. In this, Zibaya is both as an accomplice and a flâneur: not in the typical sense of a middle-class idle observer, but as an anonymous, mobile, stimulated, and fragmented inhabitant.

As for the photographs, I was making them while homeless. Capturing a shadowiness of the human figure. Specifically, not capturing the face, but something much more intimate. It felt like I was in prayer with the people. Whatever they were carrying, they were carrying me, and I was carrying them too. I think the City of Johannesburg does that, it eats you, and it spits you out. But at the same time, it also embraces you. Perhaps it doesn’t always give you a chance, but it allows you to fail.

Zibaya was born in the Eastern Cape during the country’s democratic transition in 1994. He grew up in orphanages in Durban and later moved to Johannesburg, where he was introduced to visual art, performance, and photography. The combination of these experiences is distilled, expressing an almost spiritual need to bear witness. The personal and political nature of this work is aimed at offering answers around what has always preoccupied Zibaya’s emotional and psychic life, “this formation of being a human.”

As a response to the overrepresentation of destruction, Zibaya considers how the aesthetic of vandalism is a collective act of living and communication on the ground; how the city stands in its spray-painted grit as a shining thing – a reason to venture toward something instead of recoil. Here, Zibaya is implicated in City life, noticing cracks on the wall, the collapse of buildings, the movement of migrants, Black children, Black women, and Black men engaged in daily life.

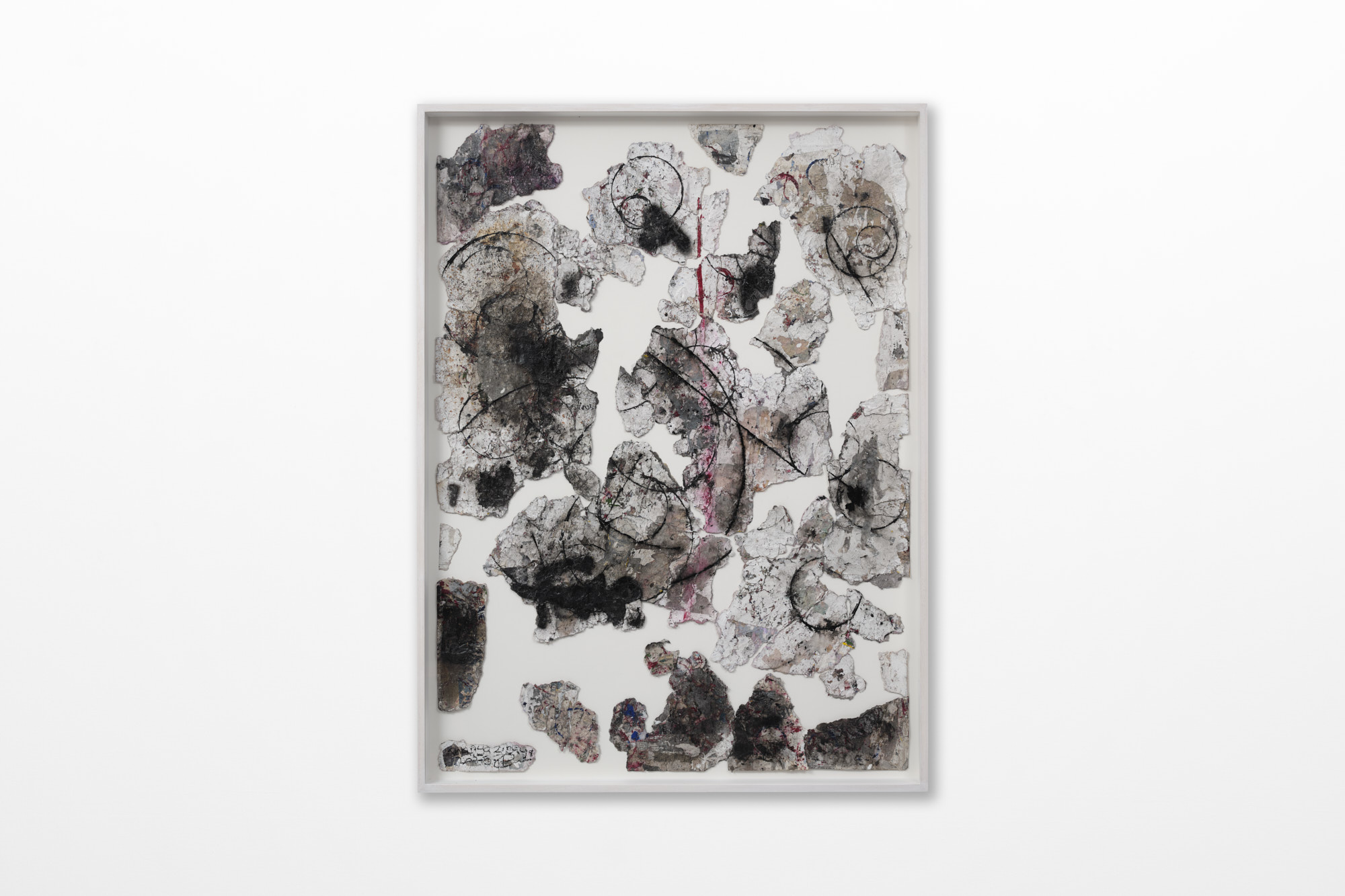

The collages, works on paper, are a new development in Zibaya’s practice, which has hitherto revolved around photography.

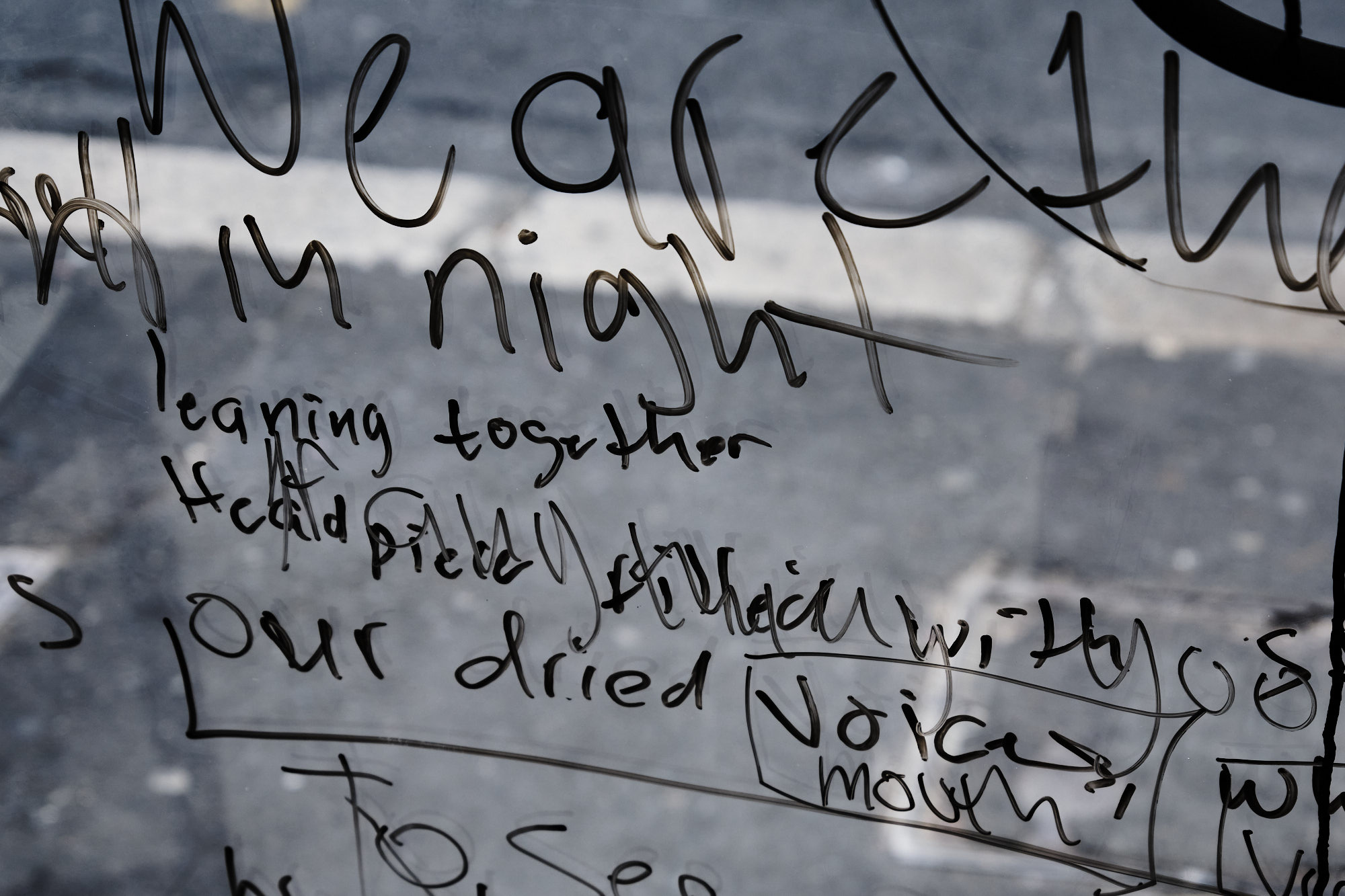

Zibaya’s abstractions emphasise a need to abuse the paper, to disregard its initial form, to disrespect it, with the hope that something else can emerge. His use of materials breaks down what ordinarily is an expensive and durable cotton paper, through water, cheap paint, spray paint, glue, and the use of flour:

It took around six months to begin to have a clear understanding of the process and what I was doing. The reference for the work on paper is the urban environment, specifically the walls. Walls are a political thing. They exist to keep someone safe, to keep people out, and to lock people in. All these things–buildings coming in, being taken over, people being pushed out, again being gentrified–the walls still hold all those memories. Over time, the sun degrades even fresh paint, revealing what came before. These layers can create something very interesting. I think of those complexities we all have and that are contained within the city.

Once you stick on paper and leave it for a while, and then come back to peel it off, ripping it, painting over it, over and over and over again, you begin to create a similar result.

This approach creates a rotting effect akin to damp and detritus; symbols printed on the currency of grit. As such, Zibaya’s process of destruction becomes a euphemism for the City and how it operates. This method of creating to destroy, or destroying to create, produces collage works that are brittle, decaying and yet fortified, much like fragments of the inner-city blues that the works encapsulate. In this process, the artist is required to seriously consider the notion of “the assemblage” as a method that might enable the emergence of multiple meanings that sometimes can appear contradictory. Fundamentally, this too is the eloquence of beauty as it intersects with our spiritual awakening.

In Akho siqwanga egoli / There are no tough guys in Johannesburg, Zibaya suggests that loitering, feeling lost, or aggressively anxious is omnipresent in South Africa’s urban life, as are expectations of men navigating the man-made. Similarly, in Ramaphosa ate my balls, Zibaya invites the use of a collective language of lament, which can be found painted over deserted walls of the City as cries and mockery – micro-acts of power and propaganda. In titling this work, the Artist expands:

I saw this phrase written once on a wall, and that for me was like protesting at the highest level. It has a sense of humour but is also layered in so much truth. The truth of the castration and what politics does to people.

I had a friend who went about the city writing, in very dilapidated areas, “I See the Future as a Beautiful Place”, and I was so inspired by that. My work is titled in that manner, trying to remain true to the place; charged, but also tied to sincerity and the space you are occupying. These ideas, of hope and pain, they are not without each other. They are occupying and living in the same space in a manner that is not opposing. Each presence is equally important. I am drawn to that kind of confrontation.

As a punctuation to the abstractions, Zibaya returns to a series of black and white photographs that he took in Johannesburg at the beginning of 2025. Adrift in the city, Zibaya photographs possibly friends, lovers, colleagues, strangers, and communities who make up the City. The figures are unannounced, yet their brevity is apparent. Like his works on paper, the monochrome surface is only the beginning, in the long durée of “the Black aesthetic” in South Africa’s visual cultures, which Zibaya partakes in and materially expands.

Walking around, although it was late at night, although I was lost, and had nowhere to be, I saw so much beauty. There was so much calmness. Shooting in a taxi, people coming back from work, and everything felt very clear. The people I saw oozed tenderness and innocence, even though the place was smelling, and the walls were decaying. At some point, it felt like life made sense. I think it was a moment of true freedom.

We are living in a world that is ugly and rotten, but also beautiful. I think all these things are necessary; the ugliness is necessary; the beauty is necessary.

We Should All Be Dead, therefore, moves beyond an over-reliance on the forms of loss and deaths that have emerged as a result of the new South African polity. Rather, Zibaya makes while listening to poets: Shakespeare, William Blake, and T. S. Eliot. These literary influences emerge and take place alongside lineages of Black intellectual traditions, where scholars such as Uhuru Phalafala and Hugo ka Canham propose that there are fragments of memory that might signal the existence of livability and beauty in the wake of colonialism and its afterlives. Moreover, We Should All Be Dead considers a morality beyond societal structures, one in which bearing witness to both big and small occurrences brings us closer to truth, and thus closer to catching glimpses of our environment, our fellow neighbours, and ourselves:

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.

…

God appears and God is light

To those poor souls who dwell in night,

But does a human form display

To those who dwell in realms of day.

William Blake, Auguries of Innocence (1863)