Vela Projects is honoured to present, an exhibition of paintings by two legends of South African art in the twentieth century: Peter Clarke and Robert Hodgins.

Comparisons can be odious, as the old saying goes. And yet we cannot help but feel that the affinities between these two artists beg to be substantiated. For starters, Clarke and Hodgins were contemporaries: both were born in the 1920s and passed away in the 2010s. While Hodgins was born in England, both artists lived and worked in South Africa for most of their lives. They are known principally for their paintings, but they also served as printmakers, writers and educators.

In the studio, they tended to work slowly and methodically, and yet both were extremely prolific. Bold, sensuous colour is the hallmark of both painters’ work, and both were passionate observers of the society in which they lived. Looking at the works gathered in this exhibition, it would seem that both Clarke and Hodgins aimed to address how the individual manifests within structures of power, although they did so from different perspectives.

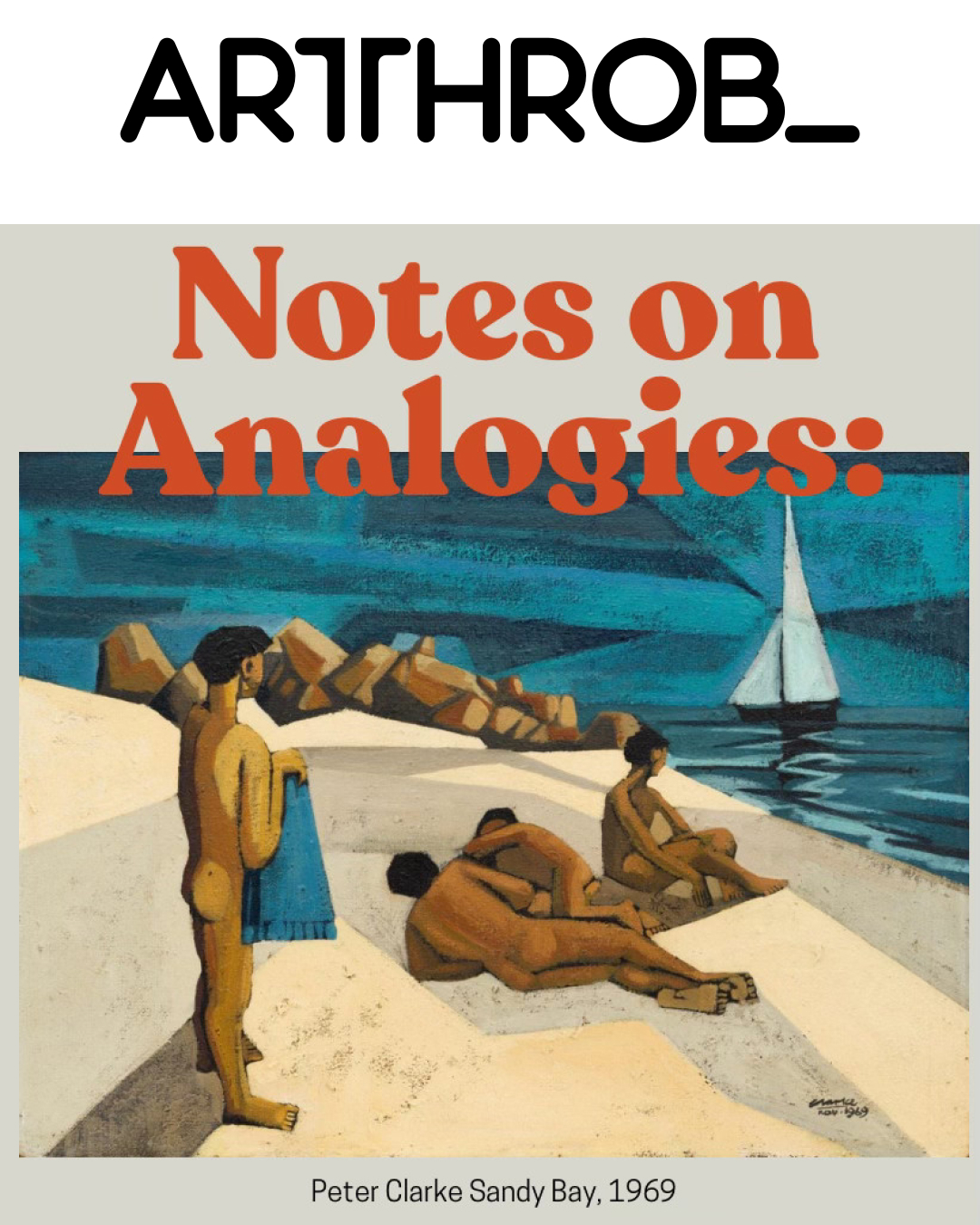

Clarke grew up in the sea-port of Simon’s Town. The men in his family were dockworkers and fishermen, and Clarke made a living painting seascapes down by the harbour after he left school at the age of fifteen. He returned to the sea as a theme throughout his career. A prime example is Sandy Bay (1969), which portrays a nudist beach on the Atlantic seaboard side of Cape Town. On the left-hand side of the picture stands a boy. He has dared to brave his buttocks to the viewer, but he still holds his towel timidly in front of his lap. He is gazing at three other boys: two are reposed (suntanning, napping, maybe even cuddling) while the third looks wistfully at a sailboat as it dawdles across the bay. While the sea is calm, and the sky is blue, a sense of foreboding haunts this image. Perhaps it is in the shame-wracked body language of the boy who wants to fit in with the reposers, but cannot gather the courage to expose himself as they do. Perhaps it is in the mournful gaze of the boy who is looking at the boat, dreaming of escape from the land to which he is bound or, inversely, cursing the ships that no doubt brought some of his ancestors to this land and bound them. Perhaps it is in the shadows that creep across the otherwise sun-dappled landscape and drape themselves over the figures.

Although it was not until 1973 that Clarke and his family moved to the township of Ocean View (which cruelly supports neither access to the ocean, nor a view) the forced removals of Simon’s Town’s coloured residents began in 1968, one year before Sandy Bay was painted. One can imagine that part of what Clarke was trying to accomplish in this picture was an affirmation of these boys’ belonging to the beach. This is reinforced by the fact that the boys’ bodies and the boulders are exactly the same colour. So too in the sand that has been sprinkled across the painting, rendering sea, sky, sand and figures texturally indistinguishable. This not only lends the composition a visceral quality, but suggests that no government, however violent, can fully sever the relationship between land, sea and people. They share a quantity and a quality. They share a skin.

This is how Clarke operates: he takes what seems to be insignificant and makes it prominent, powerful. He shows the triumphant spirit of the underdog. He does not quite empower (that would be too crude), but he does depict how defiant people can be in the face of disempowerment. He casts everyday people as heroes. This is aided by his use of sharp lines, geometric compositions and somewhat cubist figurative techniques, which lend the often delicate and reticent nature of his scenes an air of strength and solidity. The man and the girl portrayed in The Red Road (1958), a gouache on paper, offer a good example. These are not confused or porous people. They are dignified and clearly-defined. They know who they are and where they are. There is a long road ahead of them, leading to places heretofore unknown, and yet they shuffle confidently towards it. A dark sky threatens overhead, but it is lightened by the trees, with which once senses this pair shares a kinship.

Hodgins, in contrast, paints distorted figures. Take Girlfriend, Boyfriend (1987) as an example. The titular girlfriend’s face is misshapen, Munchian, while the boyfriend seems to have two foreheads, two noses and no eyes. Her hair looks like a fire; his looks like fishbones, rendered in quick, confident strokes of blue and teal. His whole face is blue, except for his lips, two pathetic little squirts of red that match the red of her body, while her lips, blue, match the blue of his face. The exchange of colour here implies an intimacy between them, but the sheer discrepancy in scale (she is so small compared to his enormous head) and background (she is posed in a white room, his is black) suggests a profound sense of alienation. This is typical of Hodgins’ work, which tends to depict characters as being trapped in their own worlds, even when they are situated right next to each other.

When he was a child, Hodgins was whisked back and forth from his mother’s humble working-class flat in Depression-era London to foster parents who lived in a huge estate in the country. He left school at fourteen and worked as a newspaper delivery boy before, on his eighteenth birthday, he landed in Cape Town with exactly six pence in his pocket. He served in the military, studied at Goldsmiths, wrote criticism for Newscheckand became a lecturer, first in Pretoria, then at Wits. It wasn’t until the early 1980s, when he undertook a project to paint scenes from Alfred Jarry’s play Ubu Roi, that he found a subject to which he could commit in earnest: “the evil clown,” as he put it, “the laughable monster.”

Who is this laughable monster? The politician, the boss, the landlord, the military officer, the newspaper editor, the academic: villains in positions of power, with whom one might say Hodgins spent his somewhat itinerant life contending. Although Hodgins begrudgingly enjoyed the privileges that whiteness afforded him during the apartheid years, he never forgot the poverty from which he fled. From this vantage point – between classes, between worlds – he could closely examine the lost souls of the upper-crust. This is how he paints them, anyway: soulless, lost. Turn of the Century, for instance, depicts a couple dressed in Victorian garb: his starched collar, her handfan. With the lights flaring above them and their gazes fixed ambivalently on a sight we cannot see, it is not hard to imagine them seated in an opera box. With his one wandering eye distracted and hers obscured by water-coloured lenses, it seems that they are more concerned with their own status than enjoying the production they have come to see. The place where his hair should be is pink, suggesting something of his two-facedness, while one of her hands is bunched into an angry green fist. Their personalities are mangled. Their identities are in disarray. But Hodgins does not paint them without empathy. Looking at the painting again, we see that there is something clownish, something comical, about their grotesqueness. It is as if Hodgins wants to reveal the child inside the costume, the fear inside the monster.

“There are paintings that stem from memory and from a sombre look at the human condition,” Hodgins once said, “paintings about the construction and confusion of contemporary urban life, but also paintings about the pleasures of being alive, pleasures that crowd in upon the pessimism everywhere – that crowd in and refuse to be ignored."

Clarke echoed him when he was quoted saying, “How amazing to be a person, to be alive here and now on the surface of this planet. So I want to, and do, express myself and my feelings of affection, frustration and resolution in the way that I do; as well as my concern, via the people who appear in my work.”

Confusion, pleasure, affection, frustration, resolution, concern – what binds these two artists is their ability to integrate these contradictory outlooks on life in compositions that continue to, by turns, disturb, fascinate and delight.