Vela Projects is proud to present Good Fortune and Prosperity, Alexis Schofield’s third solo exhibition and his second with the gallery.

The title derives from maneki-neko, the Japanese beckoning cat with a mechanical arm, which is thought to bring good fortune and prosperity to its owner. Schofield is fascinated by this talisman of artificiality which, he says, represents the paradoxical times in which we live. “We all feel a sense of despair,” he says, “and at the same time, we’re just trying to get rich.”

Indeed, it is often despair that produces the desire to get rich. “I really like this idea of these two things coming together in this mass-produced plastic cat,” says Schofield.In many ways, the maneki-neko is the ultimate token of investment in the logic of mass production, which transforms that which we can’t have—good fortune—into something that can be bought—a commodity alienated from its spiritual origins. For most people who encounter the object outside of East Asia, the maneki-neko is little more than a shiny plastic toy; as elf-contained object whose meaning bears almost no relation to reality. It is pure artificiality, in the artist’s words: “Artificiality that is not pretending to be something else. It is completely fake.”

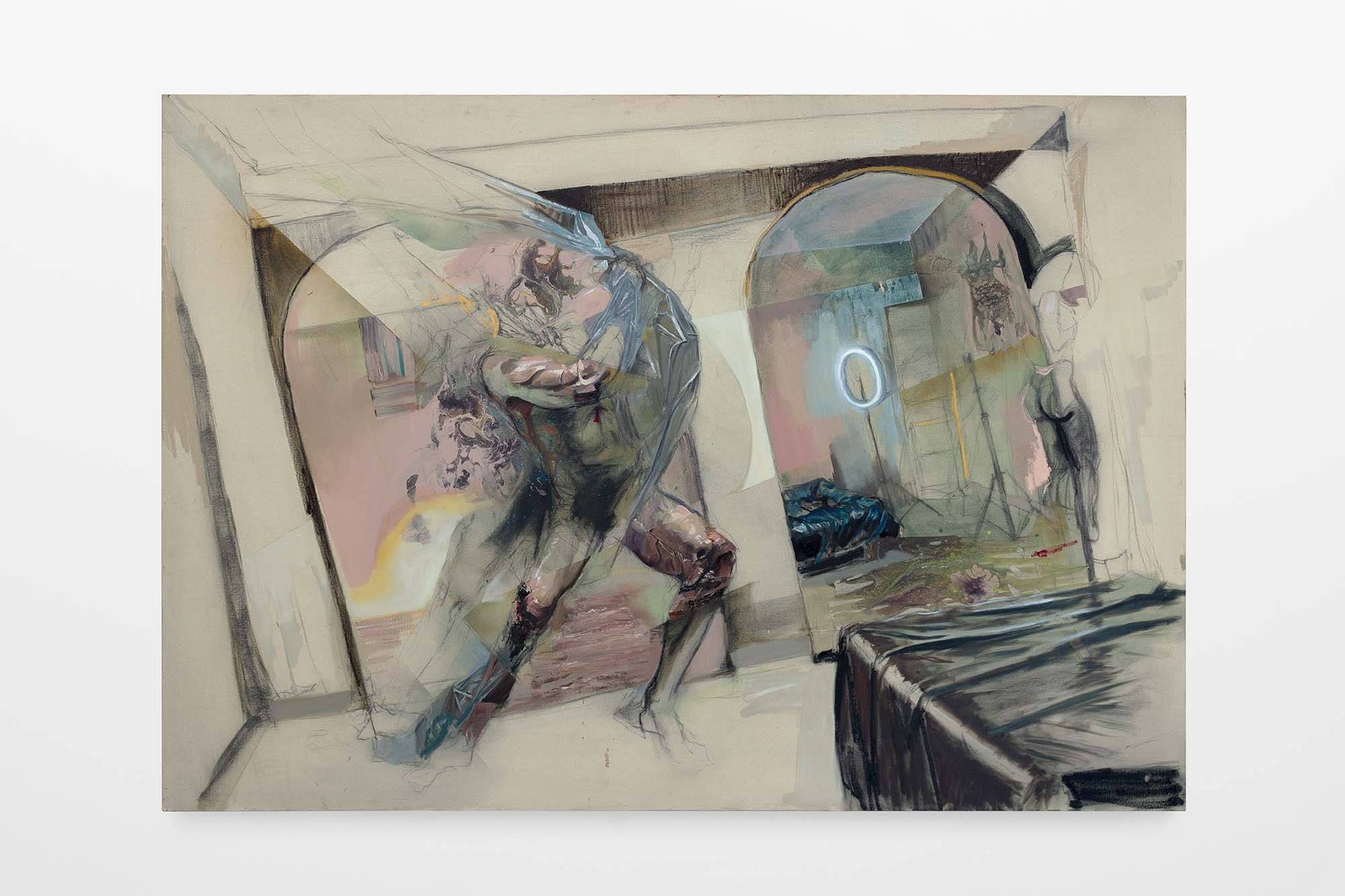

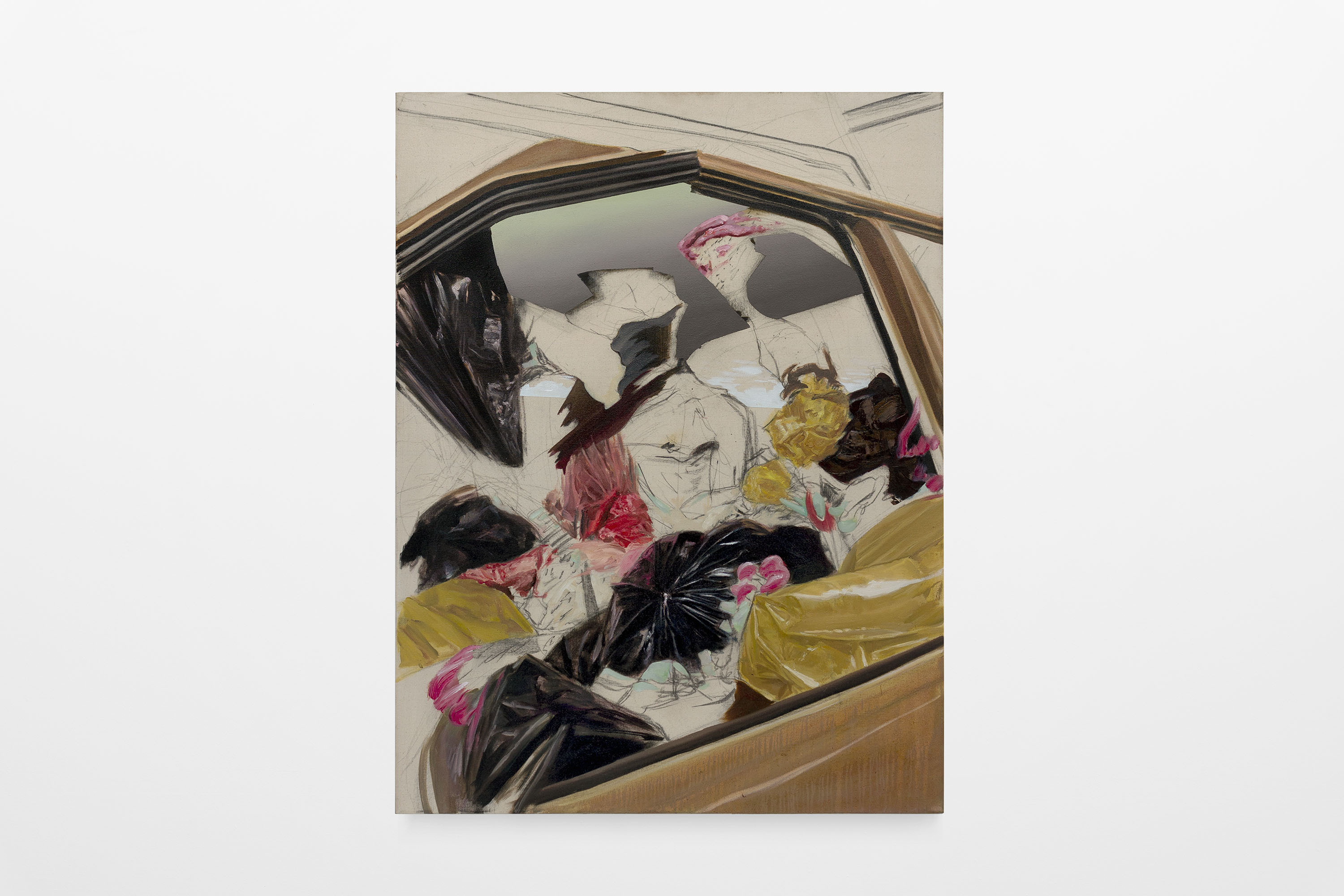

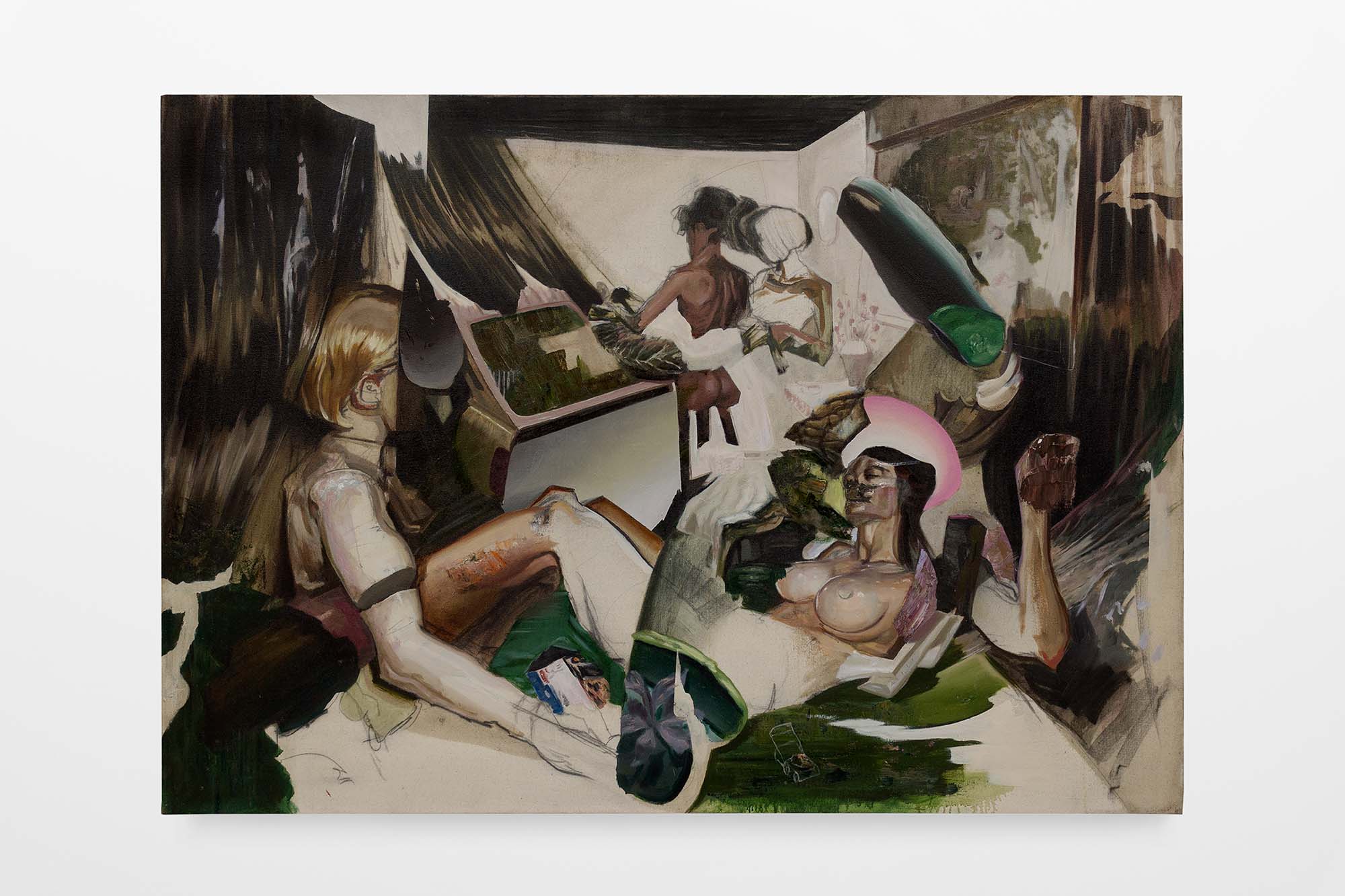

This body of work is concerned with artificiality—specifically, how we consume images in our current paradigm, as the line between artificial and real becomes increasingly blurred.To do this, Schofield paints from reference images that have undergone several rounds of distortion. First, the artist generates an image—or a series of similar images—by feeding prompts into AI. By extracting elements from its output and collaging them together, Schofield creates a new and unusual composition. He translates this to the canvas, improvising along the way with a range of materials and techniques. Eco Anxiety, for instance, combines frenetic charcoal line work with expressionistic, Chaim Soutine-style strokes alongside a cool, flat grey scale gradient as well as planes of raw canvas. The image, at first glance, is hard to digest—it might even appear abstract—but upon closer inspection, its detail scan be made out: unmistakably, that image, there in the centre of the composition, has the tension and the sheen of a bin bag.

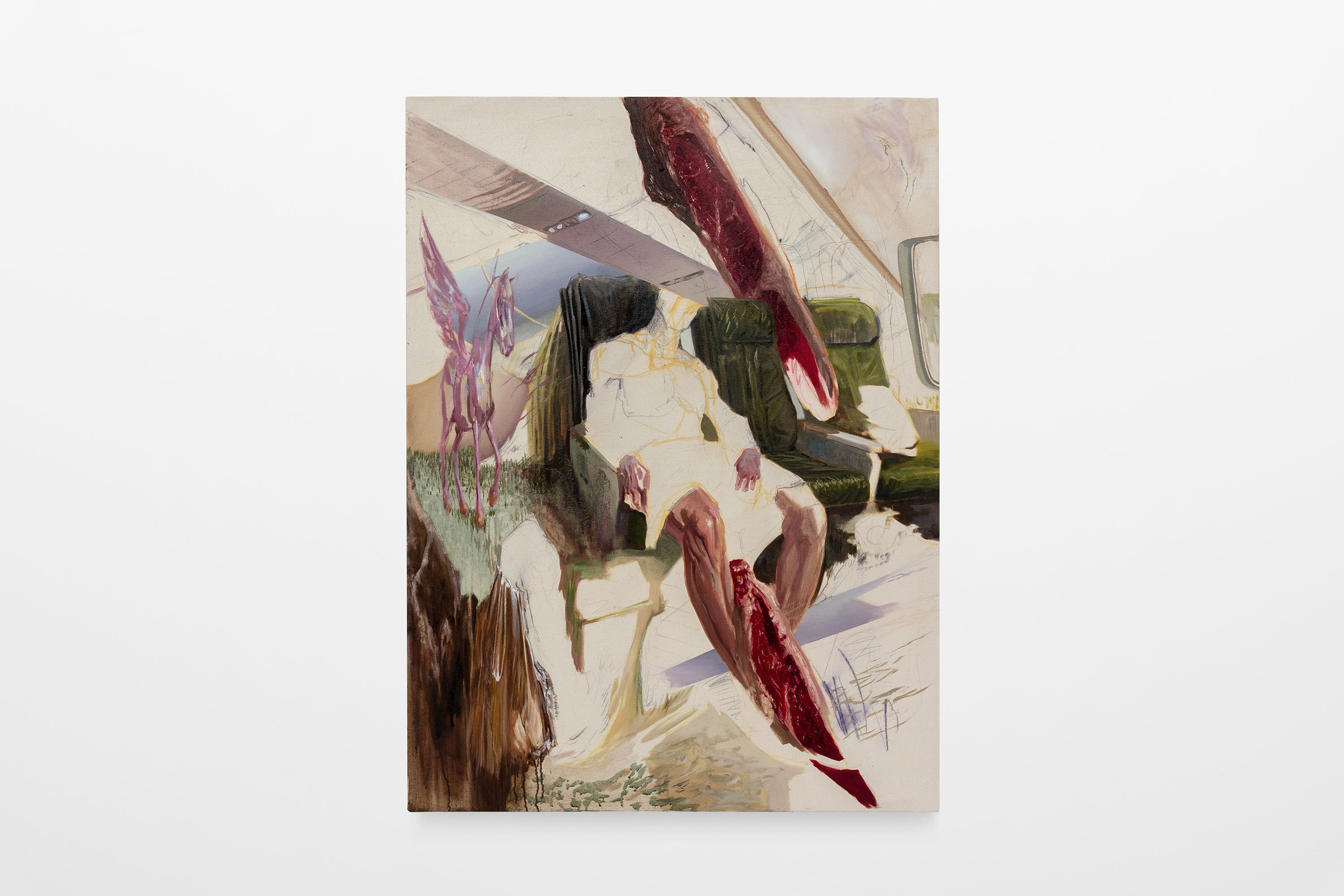

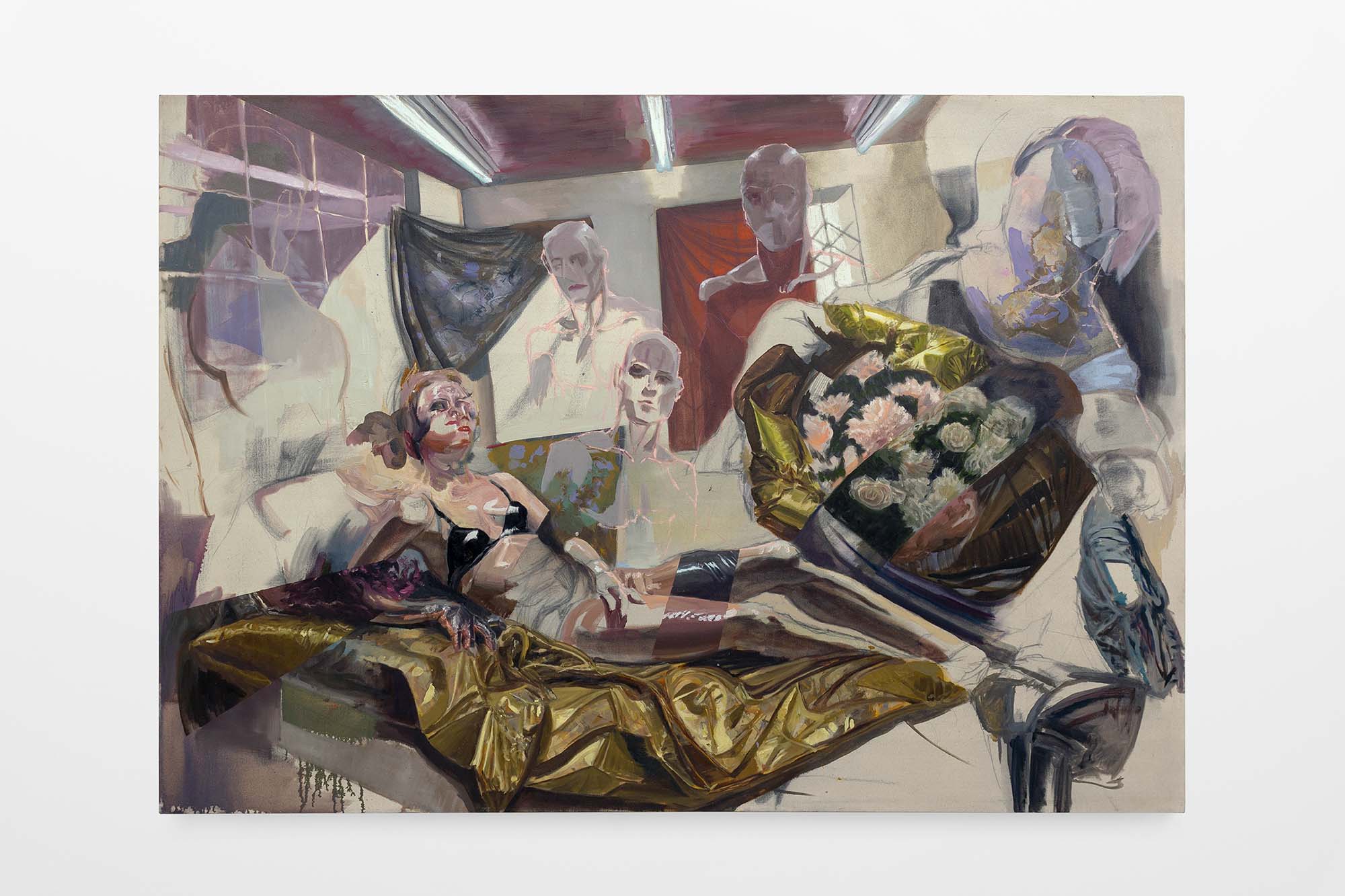

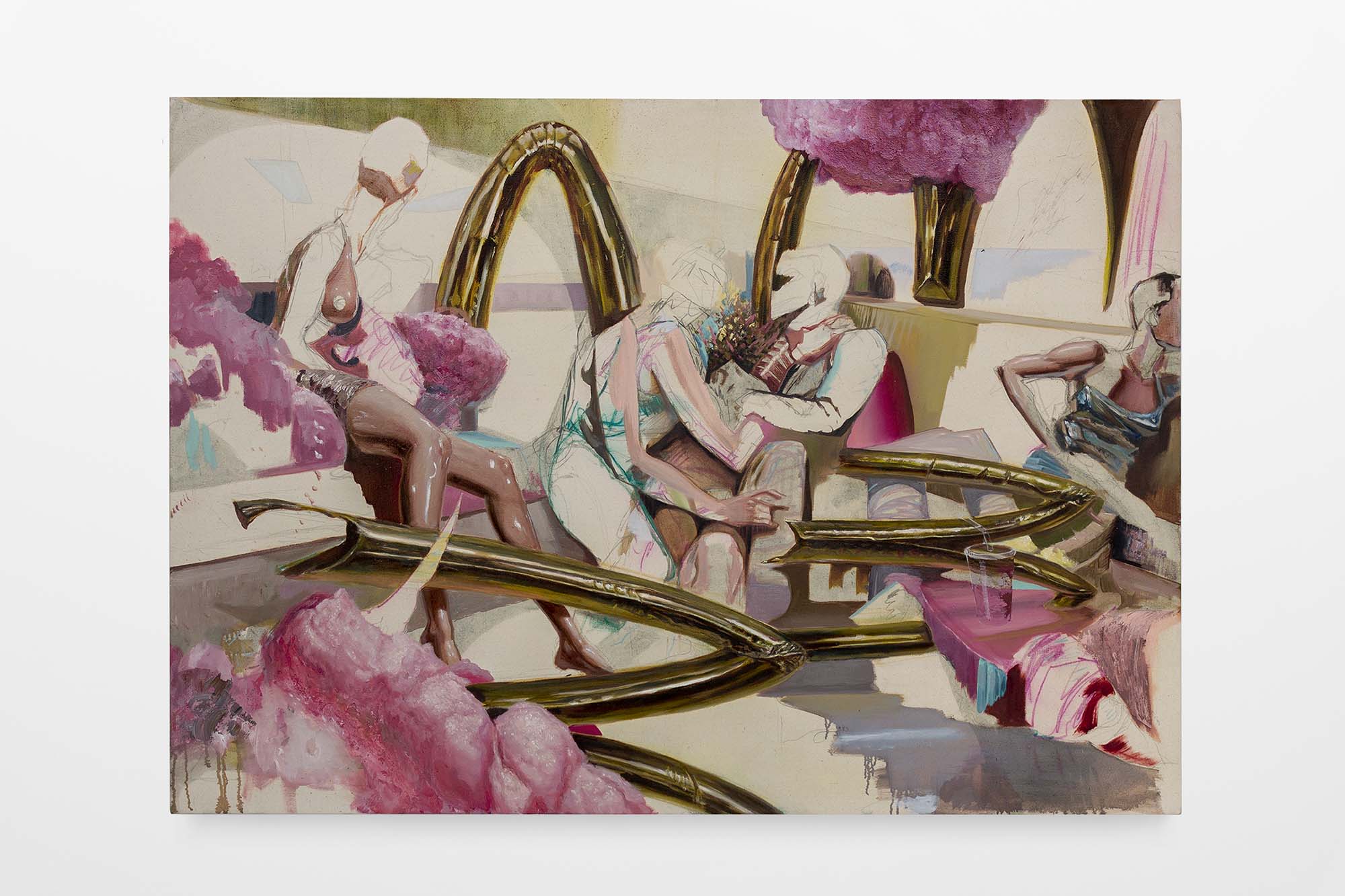

Mundane objects of the modern world—like bin bags, takeaway cups, and plastic toys—punctuate these canvases. So too do figures who appear estranged from their surroundings: the man on the airplane in EMDR is flanked by meat offcuts and a purple pegasus; the group in Left Swipe is interrupted by odd metallic tubes and ominous pink clouds. These combinations might seem, at first, discombobulating. But they speak to the ways in which we consume images in our current paradigm, which is discombobulating, to put it generously. Schofield frames it this way:

“By scrolling on our phones, we see a classical painting, a dead child in a war zone, and an advert for a nail trimmer in less than thirty seconds. These images lose their individuality and disappear into the torrent of imagery we are fed.”

It might be said that Good Fortune and Prosperity is the artist’s attempt to make sense of the torrent of images that he has absorbed:photos of friends mixed with AI-generated slop mixed with content catered to his interests. When he paints, Schofield is imitating as much as questioning the imagery he sees on social media. It is with no small amount of irony that images of the paintings will soon be uploaded onto Instagram, where they will be gazed upon for a matter of seconds before the viewer moves on to a cool drink advert or a video of cute dog.

Schofield is interested in this feedback loop, which the Internet facilitates. Instagram is catered to our lives; we, in turn, cater our lives to Instagram. This goes some way to explain why Schofield’s figures look so unreal: the left-hand figure’s legs in Left Swipe have the plastic sheen of Barbie dolls; the breasts and buttocks of the figures in Excess Modality resemble those that have been airbrushed to perfection—uncannily so—or have gone under the knife. Indeed, the artist cites the plastic surgery procedures that became popular during the pandemic as an extreme example of this phenomenon: reality is as much affected by the digital as the digital is reflected by reality. This paradigm is ouroborosian: we consume images; images consume us.

The fact that Schofield is pursuing this line of inquiry in the old-school medium of oil painting adds another layer of intrigue to the exhibition. Art historical references can be seen throughout this body of work: Manet’s Olympia appears in ENM; there’s a nod to Rembrandt’s Slaughtered Ox in EMDR; the centuries-old tradition of the still life is implied in The Smell Outside a Flower Shop on Rubbish Day. And yet, these references are so decontextualised—so removed from their point of origin—that they seem to blend more or less seamlessly into features that belong to our distinctly contemporary experience, like barred windows and airplane seats. As Schofield puts it:

“Historically images had hierarchy: a painting in a gallery would be considered more valuable than a newspaper image. Today, we are fed a constant stream of images that exist all in the same dimension, and so the hierarchy is flattened.”

Just think: up until the Middle Ages, to represent a figure required a certain level of artisanal skill:it would have to be drawn or painted. Later, it could be etched or engraved.Later still, it could be photographed and, eventually, it could be filmed. This was the point at which Walter Benjamin was writing his seminal essay “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in which he argued, “that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art.” What wouldBenjamin make of the aura of Olympia, which has been reproduced countless times the world over, fed through computer software, distorted, digested, regurgitated, then translated back to canvas again? Schofield describes it thusly:

“Figurative painting has always relied on representing the real world and in so doing reveal a ‘truth’. No matter how stylised or abstracted the representation, it was still based on a ‘real’ world. What does representational painting look like now that we can no longer trust that what is being represented is based on something real? We still understand what is being represented, as it is still recognisable, but there is no solid basis for its existence. The simulacrum is now complete.”

As such, the viewer is presented with a dilemma: first, the artworks' references are purely artificial; their only basis is in complex, otherworldly lines of code and neural networks, illegible even to their creators. Secondly, despite this absence of truth, the artworks represent something real —an interpretation of a world filled with absences. The dilemma perhaps only serves to pose the question: can such responses redeem paintings without truth, and serve a society more obsessed by image than reality?

installation images

featured artworks

Watch

Biography

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Biography

Alexis Schofield (b. 1982, Pretoria) currently lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa. Our Calves Demand a Wolf is his third exhibition, following Impressions (2023) and Feed (2023) at 99 Loop Gallery. His work has been included in a number of group exhibitions, including Sessions at 196 Victoria (2024) and Hot Spell (2023) at 99 Loop Gallery as well as art fairs such as RMB Latitudes (2024) and Investec Cape Town Art Fair (2022 - 2024).

News

Welcome to Vela Projects

Sign up for updates on exhibitions, artists and events.

Thank you! Your submission has been received!

66 Plein Street, Cape Town, 8000

Opening Times:

Tues-Fri: 11:00 - 17:00

Sat: 11:00 - 14:00

or by appointment

BOOK NOW